Introduction

Software is fundamental to the operation of digital printers, as the image to be printed is defined in software itself as a file of data. This is generally output from a design package as an image file format (often TIFF or pdf) and must be interpreted correctly by the printer to give the desired result. If the design file was printed using several different printers, results may vary widely, even if the same inks and fabric are used. Correct use of the printer software to manage colours is necessary to minimise this effect through the use of colour management systems together with the RIPs (Raster Image Processors) or printer drivers.

When specifying a digital printer for procurement, the buyer must evaluate the broad range of software and RIP solutions designed to support particular printers, as these are a key factor in the overall performance of the solution. Buyers need to evaluate these software systems and distinguish them from the printer hardware when understanding which solution or solutions can deliver the required results.

Fundamental to printer colour management is the colour gamut (the total range of printable colours) of the solution. This colour gamut depends on the printer and the ink set being used as well as the fabric and any pre- and post-treatments, as all of these contribute to the production of colour on the fabric. For a successful result, the desired colours must lie inside the digital printers colour gamut: if a printer is incapable of producing a desired colour, no amount of colour management can make it possible.

Some of the first digital printing systems introduced to the textile industry used a CMYK (cyan, magenta, yellow and black) printing process originally developed for the graphics printing industry. These systems were not well received as the attainable colour gamut is considerably smaller than the gamut of spot colour inks used in conventional rotary screen printing of textiles, and so did not meet customer expectations.

In particular a CMYK process has difficulty reproducing bright reds, greens, and blues, and can be improved by including extra colours that cannot be reproduced by mixing cyan, magenta, and yellow. For example, Hexachrome is a 6-colour process printing system developed by Pantone with orange and green inks added. Addition of colours, including light shades, to a process colour system also can help to address the other main complaint about digitally printed fabric from the textile industry - the visible dithering pattern that mars a design if not properly handled.

Colour management and RIP software manage colour by creating profiles specific to each combination of printer, ink set, fabric, pre-treatment and post-processing (steaming and washing) conditions. All of these variables have an impact on colour and each combination to be used in proofing or production must be profiled to ensure accurate colour matching. The process of creating a colour profile includes linearisation for each ink colour in the printer, which corrects for the fact that the colour effect on the final print is not a simple linear function of the amount of ink laid down. Once this is complete, a colour pattern containing a large number of colour targets is printed and used to map the colour space of printable colours using a spectrophotometer. The collected data are then used to create the finished profile.

Textile-specific software solutions

Textile-specific software is needed to handle textile design images, including flat and continuous tone designs and separation files. The specific requirements for textile printing call for some or all of the following features:

- Accept textile industry file formats from CAD design and screen separation programs: CST, MST, PUB, GRT, SEP, SCN, XPF, etc.

- Accept common graphic file formats: TIFF, Indexed 8 bit TIFF, PSD, EPS, AI, BMP, TGA, etc.

- Editing of very large image files

- Channel and image-based workflows

- Support for spot and process colours with expanded ink sets beyond CMYK

- Print layout functions such as step & repeat, multi-image placement, scaling, rotating, spooling or batching, etc.

- Colourway variations of designs

- Real time repeating

- Management of higher ink densities required for colour saturation of fabric

- Colour catalogues, colour palettes, and/or Pantone Textile Colour System

- Profiling: supplied by vendor or custom profiling capability

- Colour gamut visualisation and comparison, with highlighting of out-of-gamut colours and other print errors

- ‘Screen print simulation’ features if digital proofing output needs to match to screen-printed production

- Capability to link colour data to the textile mills colour kitchen

It is helpful to have screen simulation features to bridge the gap between digital and screen printed fabrics, especially if both techniques are still to be used. Several software vendors have incorporated features useful in simulating and matching to screen printed production fabric, such as simulating screen resolution/mesh size, colour mixing and overprinting, colour trapping, and incorporating gradation curves for tonal separations.

Other software functionality

As well as handling the image processing and colour management, printer software also has a role to play in enhancing productivity of the solution, for example by managing and scheduling jobs, optimising use of fabric, costing of ink for a job, storage of job settings so they can be reproduced later. Software can also be used to monitor the total area of fabric printed, per job or per day, for each printer.

Licensing models

For print software, several models are possible to enable purchase of the software by the user (whether the software is bundled with the printer or not). The models typically used are:

Purchase – the software is purchased outright from the vendor as a single transaction, generally including software updates for a limited period after purchase

Lease/Subscription – the user pays an annual fee for the duration of the contract and receives a licence plus upgrades and support for the contract period

Click charge/Pay as you go – in this case the software licence is monetised per ‘sheet’ or per square metre of printed fabric, meaning that a company that prints less fabric pays less for the licence (and vice versa)

The pros and cons of each model (both for the software vendor and the user) are of course different in each case. The Purchase model requires a capital investment from the user, which may require loan financing if cash is not available, whereas the Lease model allows the spreading of expenditure over a longer period – this also gives the software vendor some recurring revenue. The big advantage of the Click Charge model for users is that the software expenditure is then (like ink usage expenditure) proportional to usage, so can be accounted for as a variable cost in print cost calculations. For the software vendor it has the disadvantage that the level of up-front training and support provided is likely to be independent of on-going usage, so a low usage contract may not be economically viable.

Software contribution to print cost

While software of course is an essential component of the overall solution, the cost of the software (however this is monetised) contributes to the overall cost of printed fabric, and so needs to be taken into account when costing production, along with equipment depreciation, salaries, utilities, fabric and ink costs etc. As pointed out above, if the software is charged for on a Click Charge basis, accounting for this is rather simple. If the software was a single purchase, then it is accounted for in the same way as printer depreciation (by assuming a total number of square metres of production during the useful life of the software). For a yearly Lease, then an estimate of production per year is required. The companies interviewed for this article gave a range of single purchase licence costs of around €1,500-30,000 depending on the level of functionality required and amount of training included. For the purposes of calculation we have used typical machine productivities of 300,000 m2 (for a Mimaki TX300P-1800), 800,000 m2 (for a MS JP6) and 16 million m2 (for a MS Lario) per year, based on two 8 hour shifts per day, 5 days per week. Assuming a useful licence life of 3 years, a potential cost contribution in Euro cents per m2 is shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Typical impact of software licence cost on print cost, based on examples above

We can see that in most cases the software licence makes a very small contribution to overall costs – it is only for lower machine productivities that the contribution becomes significant (and in this case the low range software cost is more relevant, so even here the contribution is not large).

Examples

AVA CADCAM has been supplying modular software solutions for decorative printing since 1982. New products include a Structure Simulator enabling embossing, blown vinyl effects etc. to be simulated, and a Productivity Manager. The software integrates accurate colour management (of both digital and analogue printing devices) at the digital design, colouring and editing stage. Duncan Ross, Commercial Director AVA CADCAM, believes the value delivered from high quality print software designed specifically for decorative applications comes both from cost savings and additional sales. The cost savings “can be realised by comparing costs and wastage on the printer through enhanced colour management. A cost analysis for any period post-installation to the same period pre-installation will highlight the actual cost savings.” Key cost savings arise from optimising ink usage and reducing the need for repeating jobs to get correct colour matching. Investing in software with enhanced capability may also allow companies to rely less on outside suppliers for tasks such as repeats and colour separations. Additional value is driven by “increased design productivity, creativeness and meeting customer requirements” although this is harder to apportion directly to the software. AVA CADCAM currently offer single purchase or lease options but not a ‘pay per use’ model for the reasons discussed above.

ColorGATE’s Textile Productionserver includes RIP and colour management functions for DTG, roll-to-roll and shaped textile printing and soft signage. The software is licensed in a modular fashion that can be configured to run one or more printers as well as supporting finishing systems such as routers, cutters or lasers. Thomas Kirschner, CEO of ColorGATE, says that they have had conversations with customers about licensing on a per time or per job level but “it became obvious there other cost drivers which are far more relevant than the software itself”. ColorGATE software includes Ink Saver Technology, which can reduce ink usage by up to 30% (typically 15%). Mr Kirschner comments that “our software focuses on colour accuracy and consistency which mainly reduces the work needed in order to produce a certain colour quality and to match a reference quality for repeat orders”. In addition the software “provides a seamless flow from the design and creation process which allows smooth workflow and process standardization”.

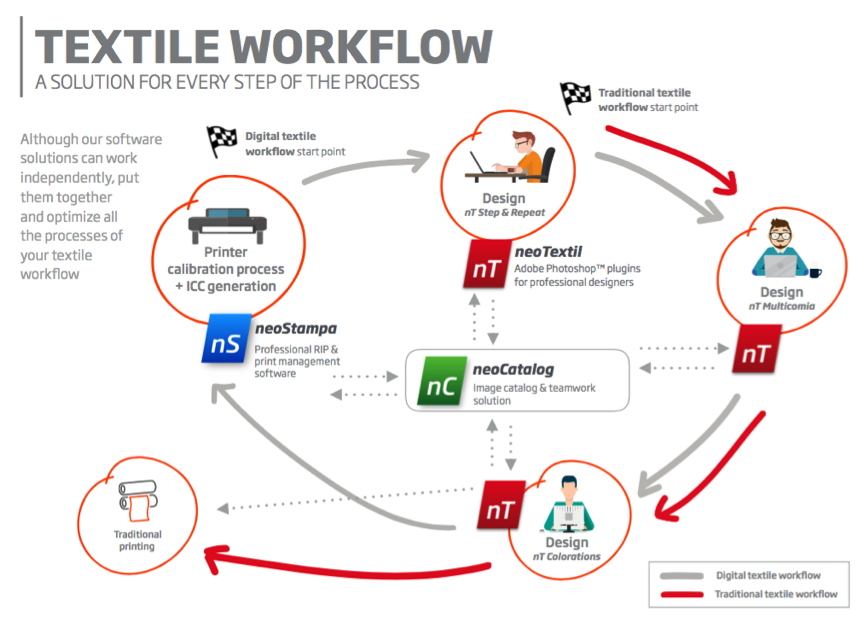

Inèdit textile software workflow

Inèdit offers a modular software solution for textile printing to fit into either a traditional or digital workflow. Its licensing model allows each module to be purchased separately, with pricing for RIP software that depends on the productivity of the printer to be driven. Victor Fraile López, Marketing & Communications Manager, says they have looked in the past at a Leasing model, but customer feedback led them to remain with the Purchase model, with the modularity giving great flexibility for customers to manage costs. For Mr Fraile, the value of Inèdit RIP software lies in “being able to guarantee an impeccable colour match between the designs or the samples printed in paper or directly seen on the screen and the final production [which is of] vital importance in the digital textile production workflow”. The Inèdit productivity software solutions, give value “in the improvement of multiple design and management processes as well as in their total integration”.

You can find out more about digital printing software at the Inkjet Printing Software course being held at our Inkjet Winter Workshop in Valencia, 22-16 January 2018.

This article was originally published in Issue 6: 2017 of Digital Textile Magazine, where Dr Tim Phillips is Consulting Editor.